Even by the standards of Sydney crime figures of the first half of the 20th century, Sidney Patrick Kelly was particularly vicious. A member of the so-called “razor gangs” that terrorised the inner suburbs of Australia’s largest city, Siddy (as he was known), slashed, shot and bashed his way through his many enemies and, occasionally, even his friends. And that was just the men. For women who fell victim to his short, volcanic temper, he arranged even harsher retribution.

Readers of Larry Writer’s Razor volume may vaguely recall him although he was, at best, a peripheral character. So, too, within the highly-romanticised mini-series that inevitably resulted, screening as Underbelly: Razor in 2011.

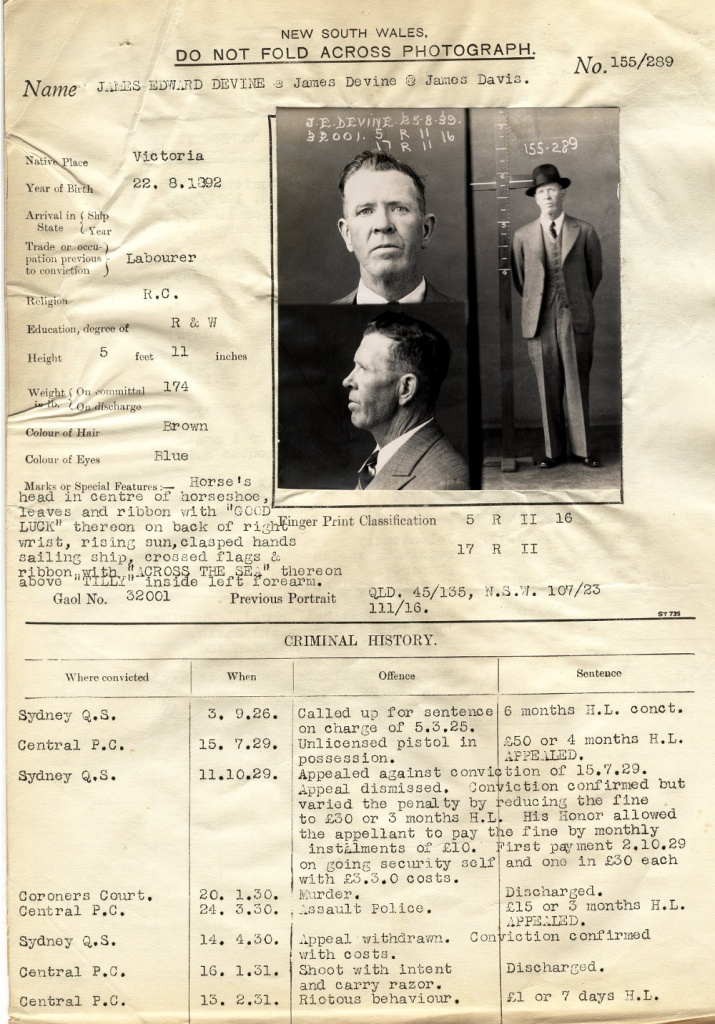

Siddy Kelly was an associate of Kate Leigh, Tilly Devine, Nellie Cameron, Guido Calletti, and even infamous Melbourne gangster, Squizzy Taylor.

Standing just 160cm, he always had something to prove and even much bigger men moved, and spoke, carefully in his presence. Early in his career, he was a cocaine dealer and police informer; gradually, he gained a fearsome reputation as an enforcer.

What he lacked in stature, he compensated for with a mercurial unpredictability. Siddy ran with a bunch of equally tough, though much larger, friends. Amongst them was his elder brother, Tom.

They were a fine pair, the Kelly brothers though Siddy seemed to have a slight edge on Tom in the cruelty stakes. The gang muscled their way through the Sydney underworld, restraining Siddy’s targets while he ceremoniously unfolded his straight razor and deeply sliced a face or, if negotiations had progressed beyond all resolve, a throat.

As a boy, he worked as a jockey and remained fascinated by horseracing throughout his life. He owned racehorses but was caught out with batteries under the saddles of some of his mounts and banned from the sport. Later, he operated illegal baccarat dens.

At the peak of his activities during the 1940s, his share of the profits amounted to around £1,000 a night (about $72,000 in today’s dollars) In comparison, the average weekly wage in 1946 was £6/9/11 (6 pounds, 9 shillings and 11 pence – somewhere around $470 in current terms).

In 1947, Kelly and his wife, Theller Omega, known as Poppy, moved to grander surroundings. A two-storey mansion at 2 Martin Road, Centennial Park, adjacent to the parklands and within sight of the Sydney Showgrounds, was purchased for £8,500 (about $615,000 in today’s dollars).

Located on a 1948 square metre block and including extensive gardens, the house had been built around 1919 in the then-fashionable Inter War Free Classical style. It was designed by the prestigious Sydney architectural firm of Burcham Clamp and Mackellar.

At the time of Kelly’s purchase, the mansion was known as Babington. Later, and perhaps as a result of its notoriety, it was renamed Stanton Hall.

A gangster moving into the silvertail suburb of Centennial Park was notable enough to attract significant press coverage. Kelly didn’t shy away from the limelight. One newspaper quoted him as saying: “I have had a pretty busy life. I figured it was about time my wife and I had a slice of reasonable comfort in a home where we will not be cramped.

“I have always wanted a place where I could put up my friends and guests, and I have always wanted gardens, lawns and fishponds,” he continued. “The place is a good investment, and I have always said that nothing is too good for the Kellys.”

He continued to make money hand over clenched fist, primarily via his baccarat operations or gambling on horse races. Yet, a huge fortune and glamourous home could not inoculate Kelly from the vagaries of fate.

On the evening of Wednesday 1 September 1948, Siddy Kelly complained of not feeling well. The next morning, brother Tom went to his room to check on him but found him dead. An attending doctor listed his cause of death as heart failure. He was just 49 years old.

Dozens of journalists camped outside his home. One newspaper dryly noted he was “a well known figure among the exotic elements of Kings Cross”.

His funeral was held at Botany Cemetery. It was a private ceremony, attended by no more than 50 mourners including Poppy. Press coverage mentioned the floral tributes, estimated at £300, that adorned the casket as it made its way from his Centennial Park home.

Of all the mysteries associated with Siddy Kelly (principally, how a man with so many enemies had managed to stay alive so long), one final mystery was about to kick into high gear.

On his death, Kelly was said to have squirrelled away between £50,000 and £100,000 ($3.5 – $7 million in today’s dollars). Keep in mind, Kelly’s five-bedroom mansion on the best street in the suburb had cost less than £10,000. A police source was quoted as saying: “He was a man who never gave money away.”

On rumours that some of the money had been buried in Centennial Park, gangs of crims armed with shovels and flashlights spent weeks digging indiscriminately throughout the extensive parklands, all to no avail.

Sensing a windfall, the Taxation Office descended but were perplexed to find that the gross value of the estate barely grazed £8,800 ($637,000 today). Net worth was just £2,768 (just north of $200,000 today). It didn’t help that Siddy’s long-time solicitor, Harold Joseph Price, had earlier in 1948 been sentenced to 12 years in jail for misappropriating clients’ funds.

Although Price had stolen some £34,000 ($2.5 million today) from a number of accounts under his care, the general consensus – in the underworld and elsewhere – was that he wouldn’t have been so stupid as to steal from Kelly himself. The money was out there, it was felt, but nobody knew just where. And it was never found, despite the best efforts of the police, the tax office and Sydney’s criminal elite.

Babington, later known as Stanton Hall, today remains largely in its original state, though undoubted refurbished many times since. It was last traded in 1976 for $90,000 and is today estimated to be worth in excess of $10 million.

What happened to Siddy Kelly’s fortune will probably never be known. As to Poppy Kelly, that is also somewhat of a mystery although just a few years later she was briefly listed as living in much humbler surroundings in nearby Randwick. There is only one mention I’ve found so far on an electoral roll for Poppy. That’s not to say there’s aren’t others; I just haven’t found them yet.

However, if Siddie had stashed away a substantial amount of money, maybe – for whatever reason – he hadn’t got around to telling his wife about it. How long she remained in Babington remains a mystery as well.

But a visit to Kelly’s grave deepens the mystery somewhat. What was formerly known as Botany Cemetery is now the Eastern Suburbs Memorial Gardens. Close to the shores of Botany Bay and today encompassed by heavy industry and maritime and port facilities, it opened in 1888. The area was traditionally sandhills which, even today proves challenging to excavating graves.

I was hoping to find that Poppy shared her husband’s grave (by which I could then confirm her name) but that wasn’t the case. Kelly’s grave was in an older part of the Roman Catholic section and, unusually, the burials along this particular row occurred by date, beginning in early September 1948 and running until late in the month. It was the only row I could find where this occurred.

The headstone was also of interest. Probate was granted on Siddy’s estate in the first week of November 1948, by which time the word had well and truly circulated about the dire state of his finances. It was just eight weeks after his funeral and probably about the time a headstone was ready to adorn his grave.

Yet the granite headstone misspells Kelly’s name. It reads Sydney Patrick Kelly. Could this have been Poppy extracting an enduring revenge for her husband’s failure to provide for her?

Maybe another clue lies in the Biblical quote included on the headstone.

“God forgive them for they know not what they do.”

I was first drawn to the story of Sidney Patrick Kelly back in early 1989. At that time, I was working away at the Mitchell Library, Sydney, most likely researching one of my books; from the date, it was Sand On The Gumshoe: A Century Of Australian Crime Writing, published later that year.

All the books I worked on during that decade (and into the next) necessitated extensive research at the Mitchell Library so it was very much a home away from home. In fact, I’d been a regular there since 1979, when I started writing for various encyclopedias published for Rupert Murdoch.

Before the universal prolificity of computers and the internet, historical research was libraries and card catalogues. In the process of looking for one thing, I often found something else equally or even more interesting. In this case, it was an article on Siddy Kelly published in People, an Australian news and general interest magazine from 1955.

I have no idea what I was initially searching for. It may have been something about Arthur Upfield, creator of Bony, the indigenous Australian detective. Or Carter Brown, the pen name of Alan Geoffrey Yates, credited with almost 300 pulp crime novels and novellas from the mid-1950s on. Or maybe even Berkeley Mather, English-born but Australian-educated, a now-almost-forgotten creator of eloquent spy thrillers who also co-wrote the script to Dr No, the first official James Bond movie, and did uncredited rewrites on From Russia With Love and Goldfinger.

Difficult to know but somehow I stumbled across this People article on Sidney Patrick Kelly and thought it’d be interesting to follow up at a later date. So, risking a hernia, I lugged the bound quarto volume of People magazines to the Mitchell Library’s copying department (self-service photocopy machines being some years in the future).

At a later date, I received from the copying service photographic negatives of the relevant three pages (can’t recall why it would have been photographed and not photocopied), which went into my desk drawer, survived several home relocations and various major and minor life changes, until I dug the negs out last week and determined it was about time I did something about the article.

Only took 33 years. Pretty good, considering.

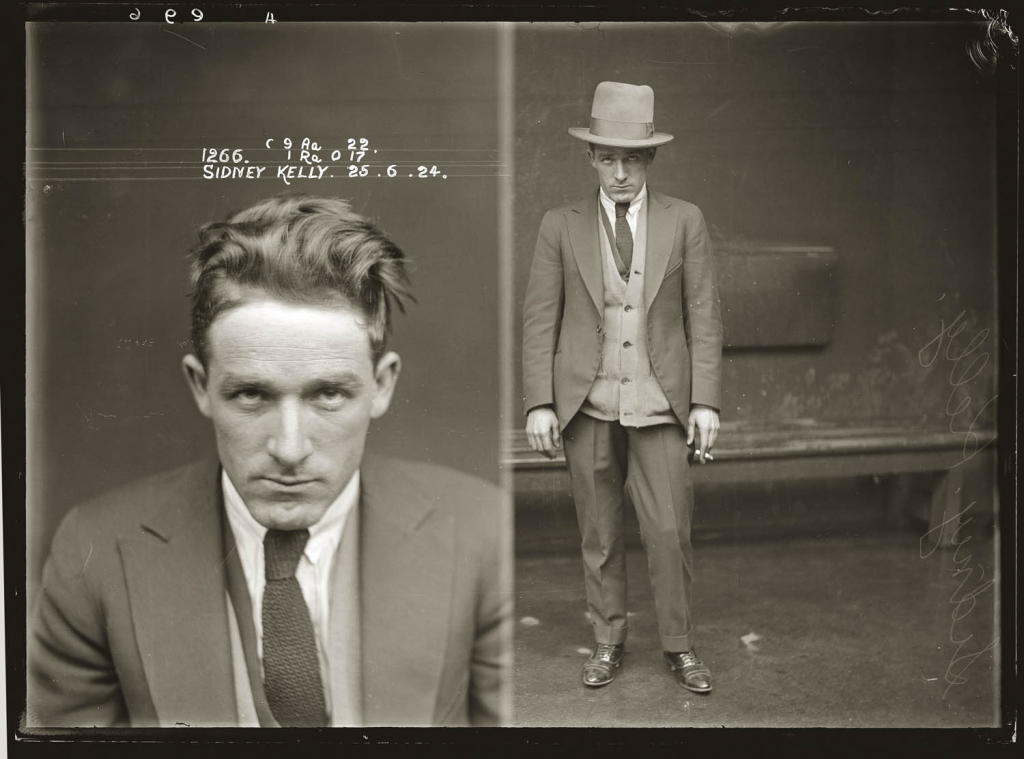

However, there is a coda to Siddy Kelly’s story. The opening photograph of Sidney Patrick Kelly, with his blue-steel gaze and snappy attire, comes from the collection of the Justice and Police Museum in Sydney. It is part of an archive encompassing more than 100,000 mug shots, crime scene and related photographs from the NSW Police Department.

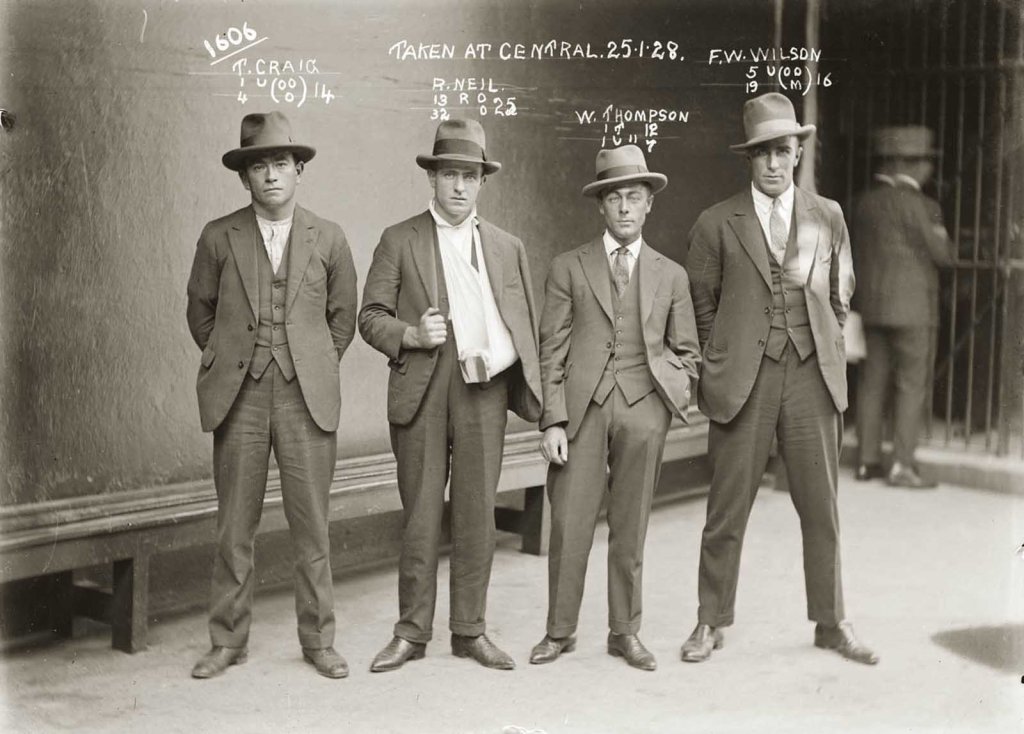

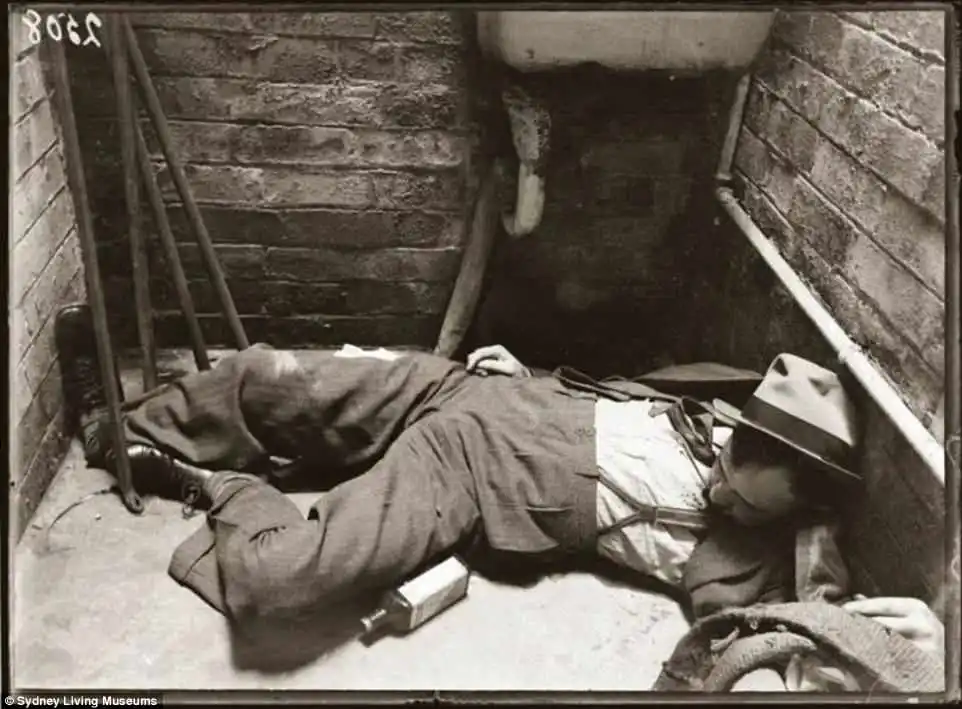

Included are some 2,5000 “special photographs” taken of prisoners at Central Police Station, Sydney, between 1910-25. These photos are remarkable, shot on large-format glass negatives. The subjects were allowed to pose as they wished in quite informal settings, totally unlike traditional institutionalised mug shots.

This photograph of Kelly was taken on 25 June 1924 and appeared in the NSW Police Gazette. It was captioned “Illicit drug trader. Drives his own car, and dresses well. Associates with criminal and prostitutes.”

Museum curator Peter Doyle (a crime writer of note, although he arrived too late on the scene to be included in Sand On The Gumshoe), collated some of these highly atmospheric photos for publications under the titles City Of Shadows: Sydney Police Photographs 1912-1948 (2005) and Crooks Like Us (2009).

The books were an outstanding success in Australia, deservedly so, although their influence extended even further. In 2011, the Justice and Police Museum was approached by the corporate head office of Ralph Lauren in New York. They wanted to licence images from the collection, notably the “special photographs”, to be enlarged to wall-size murals for display in their New York City and London flagship stores.

The Siddy Kelly photo at the beginning of this blog was one of the photographs selected. It’s interesting that a man as essentially evil as Sidney Patrick Kelly would continue to exert an influence on popular culture so long after his death.

Befitting the modern era, Kelly had become a commodity. A sharp dresser with the promise of danger in his level gaze, he was now the personification of edgy fashion. Perhaps it would have amused him. Certainly his acquaintances would have had a laugh.