Rocky Horror, the musical stage show and the film it spawned, is so ubiquitous that it’s difficult to imagine a time when it was unknown and nobody had any idea what to expect.

But so it was in the Australia of early 1974. The original live production had opened in London a year before, and the film that we now know so well wouldn’t come into being until later in 1974 and premiere pretty much unheralded and unloved late the following year.

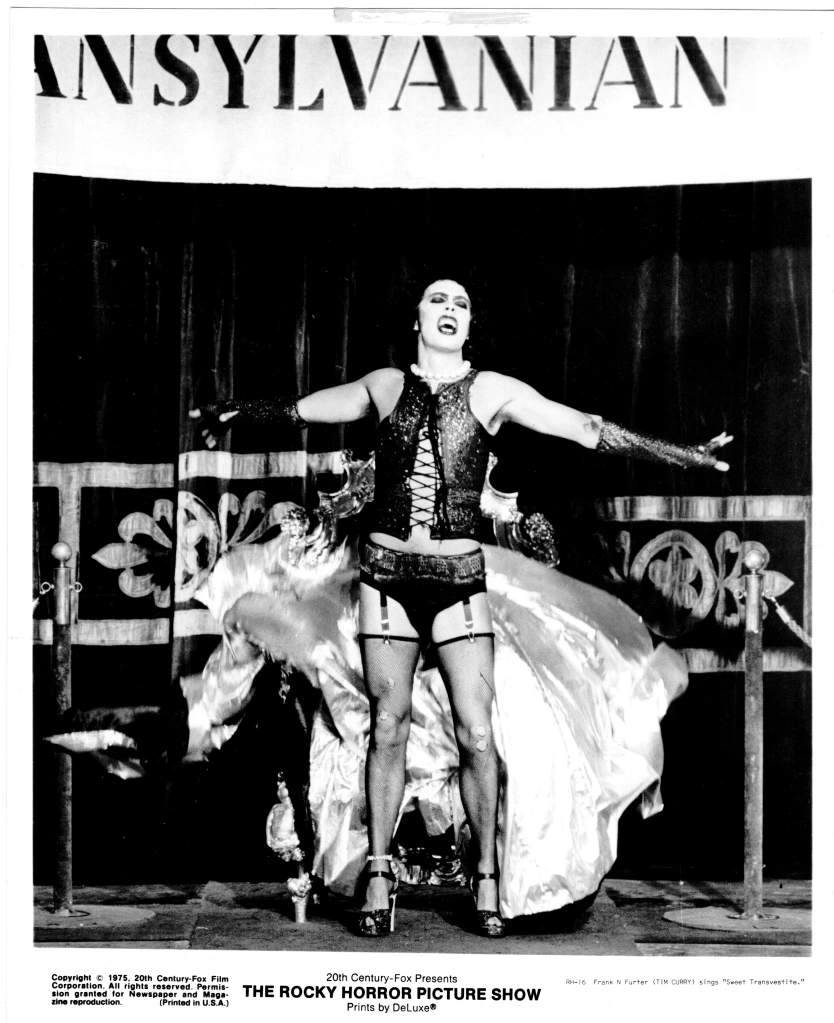

It was great when it all began, as Little Nell sang in both the London production and the film, but nobody was yet a Frankie fan. They would be, they most certainly would be. The world would be eternally transfixed by the most famous sweet transvestite ever created, and by Tim Curry, the actor who would forever be associated with the role.

But at that moment in time, in early 1974, the universe was stumm. Australians were preoccupied with other things. While youth revolt and social progressiveness had local matrons clutching their pearls, Australia was still a largely quiet and well-behaved corner of the British Commonwealth.

Heart-warming family shows, such as The Waltons (and, later in 1974, Little House On The Prairie) dominated television ratings, and the biggest radio hits came from Perry Como, Tony Orlando, and The Carpenters. We could hear music but we couldn’t see it just yet; Countdown and Sounds wouldn’t start airing until late in 1974.

There were, however, glitches in the matrix, disquieting early indicators of where society was heading. Number 96, with its nightly serving of nudity, sex and drugs, was the highest rating local television show. The Rolling Stones were in the music charts and Suzi Quatro was having the first of many hits. Queen arrived at the Sunbury rock festival for its debut Australian performance, and was booed off the stage. And the socially progressive Labor Party under Gough Whitlam was in charge of the country after decades of conservative political leadership (but that would soon crumble).

If you lived in Sydney, and scoured the local newspapers and magazines, and maybe had a few friends in the arts, you may have been aware that a new musical would soon be opening. But the name, The Rocky Horror Show, offered very few clues. And in the early 1970s, with four televisions channels, a handful of newspapers and no internet, that was about all you could find out.

It wasn’t The King And I or West Side Story. It wasn’t your maiden auntie’s musical. About all anybody knew is that this Rocky Horror thing was being produced by Harry M. Miller, who had become quite the local celebrity by mounting Hair and Jesus Christ Superstar.

Whereas, Harry had parked his previous hits in some of the largest theatres then available in Sydney – Hair at the Metro in Potts Point, and JC at the Capitol Theatre, edging Chinatown – the venue for this new musical was, to say the least, unconventional.

It was a small, grungy, rat-ridden 1940s-era former cinema called the New Arts. It was mid-way up Glebe Point Rd, in the very middle of where very few people ever went voluntarily and certainly not at night.

So The Rocky Horror Show was something of a mystery. Newspaper editors scrambled for answers, sending forth entreaties to UK correspondents for more information.

I have a clipping from one Sydney newspaper but no way of identifying which. I’m leaning towards the Sunday Mirror, the weekend edition of a Sydney afternoon newspaper fashioned on the UK’s News Of The World. It didn’t quite have a Page 3 girl on every page but its editorial tone implied such. Prurient is probably the best word to describe it, with its breathless coverage of salacious divorce cases and sex trials.

The article appeared in the weeks before the premiere of the Sydney production in April 1974. Reporting from London, journalist Graham Bicknell opined The Rocky Horror Show “…is certain to rock the wowsers of Sydney’s theatre scene.”

It was, he continued, “…complete with nudity and simulated sex acts (some natural, some not)…” He called up comparisons with Alice Cooper, saying “The stock-in-trade…is blatant shock and this show, as the title suggests, has plenty in store.” Still, he noted, “It’s high-camp teetering near the edge but never quite reaching vulgarity.”

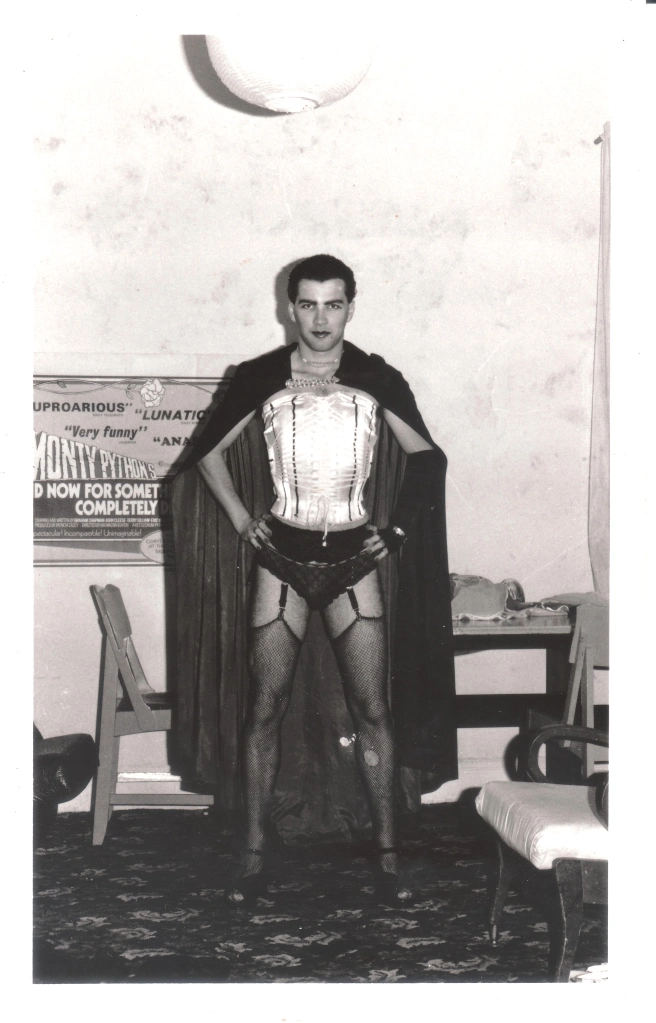

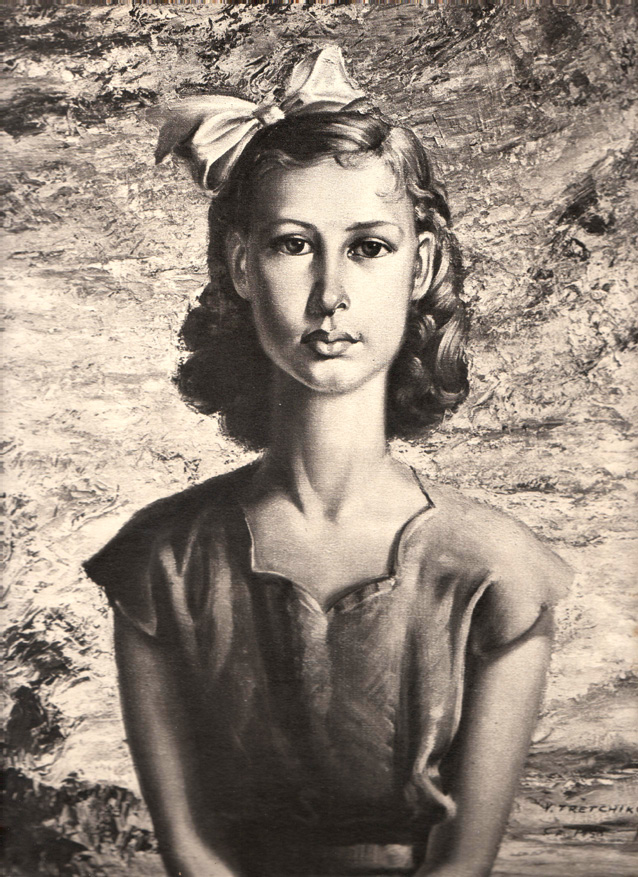

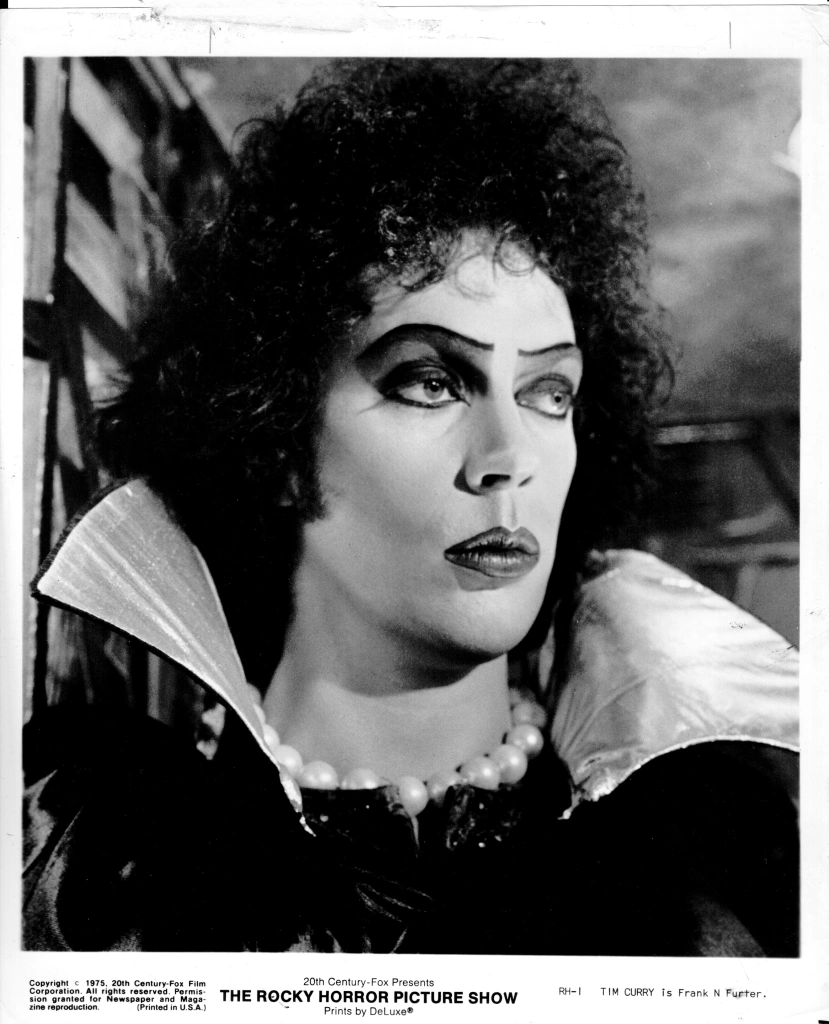

The general tone, as well as a few details, eluded Bicknell, who may have downed a few too many pints of warm lager before the show. He identified the main character as Frank-N-Further, and backgrounded him as “…a David Bowie in silk stockings, black suspenders and corset.”

By now, it’s easy to imagine the grand dames of theatre-going tossing their newspapers aside in alarm. And reaching for the telephone to book tickets.

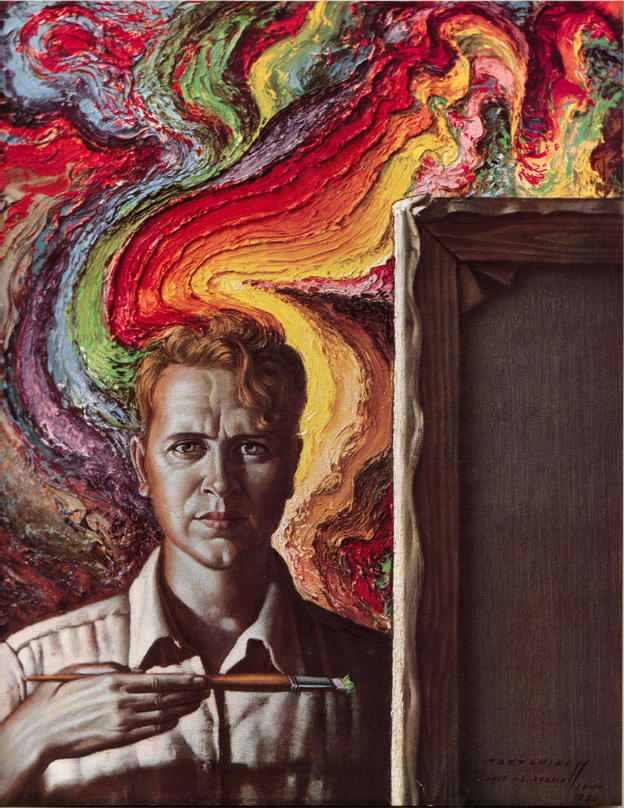

The article featured photos of Philip Sayer, who took on the London role when Tim Curry transferred to Los Angeles production. Sayer, and the subsequent actors who rotated through Rocky on the London stage at various theatres, are now all pretty much forgotten and it’s near impossible to find their presence on-line.

But from Bicknell’s article, it appears the raw sexuality that Curry engendered in the role, went with him to sunnier climes. Sayer looks more like ZaSu Pitts than Joan Crawford.

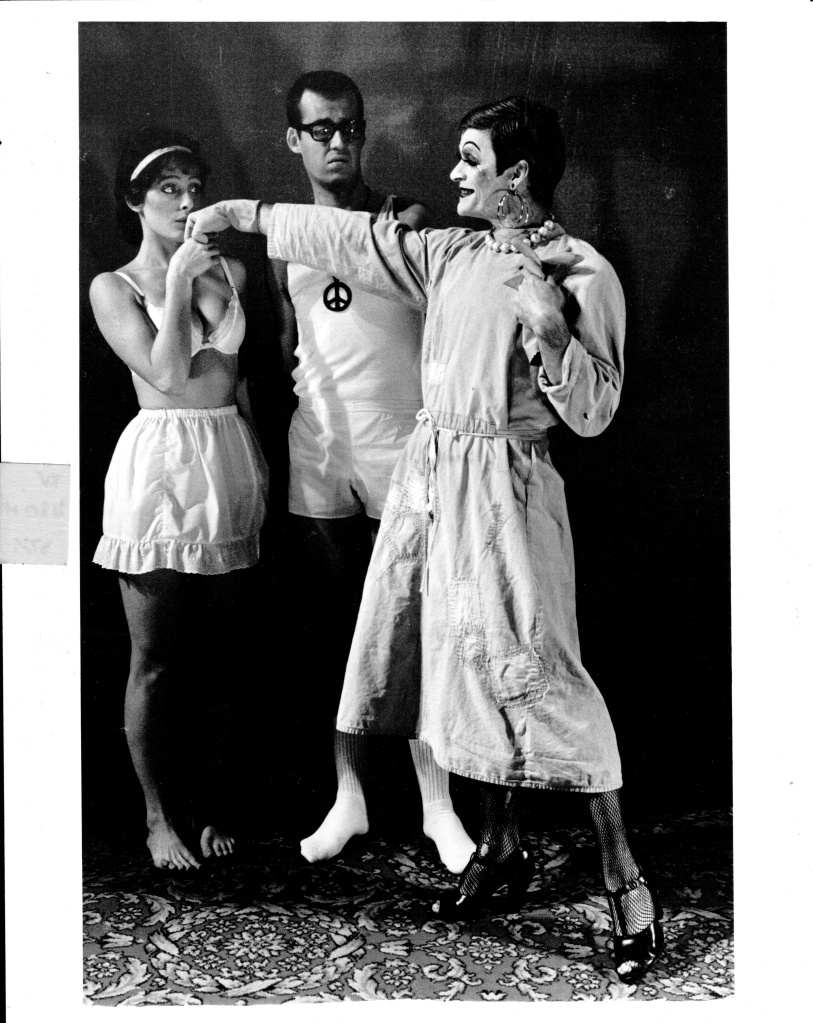

In the meantime, preparations continued for the Sydney production. The cast was virtually a who’s who of Australian theatre and entertainment. Kate Fitzpatrick played Magenta while Arthur Dignam took on The Narrator. Other cast members included Maureen Elkner as Columbia, Jane Harders (Janet), John Paramor (Brad), Sal Sharah (Riff-Raff), David Cameron (Eddie/Dr Scott), and Graham Matters (Rocky).

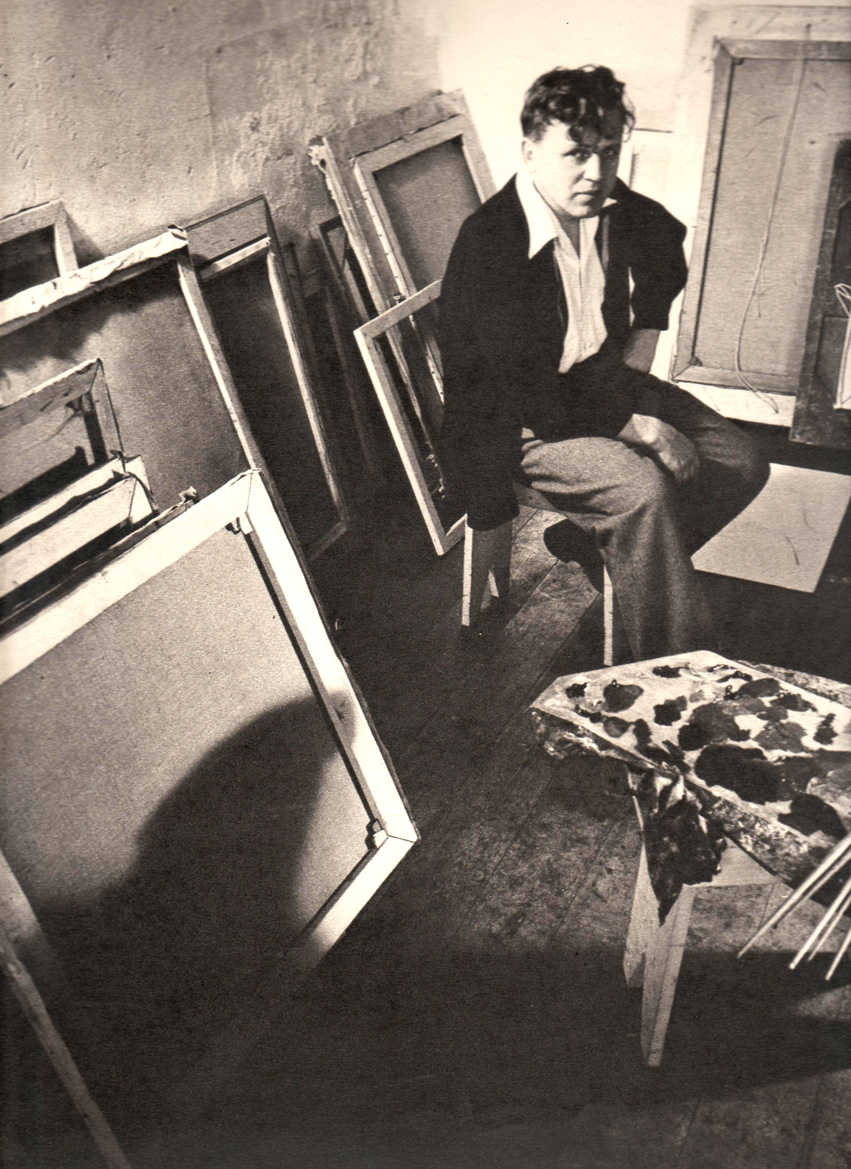

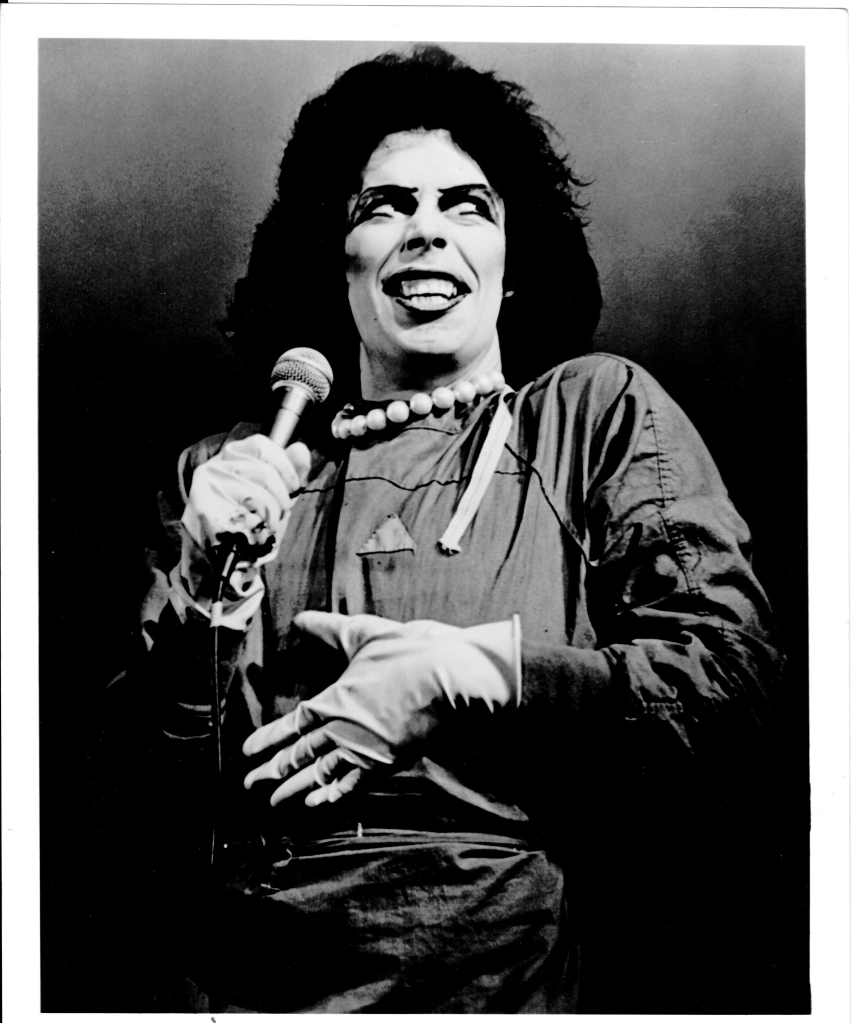

But the star of the show was Reg Livermore as Frank. Those of us who saw that production in the 18 months it ran within the art-directed demolition site that was the New Arts Cinema at Glebe, experienced something very special. I was one of those, returning numerous times.

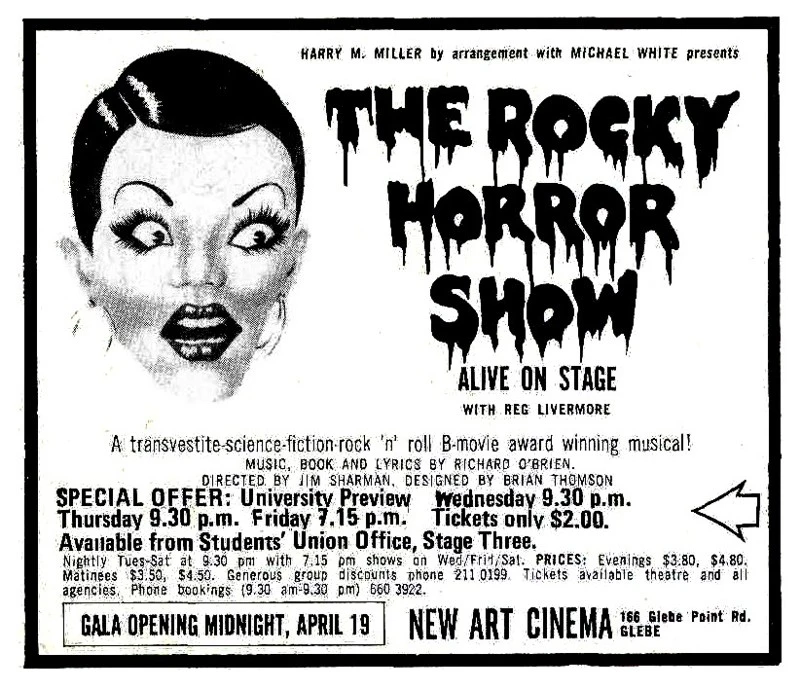

I’d been intrigued enough by the print ads that began to appear, in mainstream newspapers as well as whatever indie and youth press existed at the time; Honi Soit, the student newspaper of the University of Sydney, which itself knew a thing or two about scandalising uptight Sydney society, offered up discounted tickets of just $AU2.00 (regular tickets were $AU3.80 to $AU$4.50).

The tag-line for Rocky Horror: “A transvestite science-fiction rock’n’roll B-movie award-winning musical” was intriguing. Especially for a teenager fresh from the sleepy suburbs who had only recently discovered what life could offer in the big, bad city.

It would be another 18 months before The Rocky Horror Picture Show started in Sydney (in December 1975; a very slow roll-out for a film that had quickly been written off as a huge flop by the studio. It had premiered in the UK in August and the US in September) so nobody in Australia knew of Tim Curry or had any prior references to draw on.

So Reg Livermore blew audiences away, so incandescent was his characterisation. What we didn’t know is that Reg was also very much in the dark about the role and its predecessor.

As recounted in his autobiography, Reg Livermore – Chapters and Chances: “Nobody knew anything much about the show; reading the script didn’t help, and the scant information dribbling our way only added to the intriguing sense of bamboozlement.”

Reg already came with considerable recognition from previous roles. In 1970, he’d taken over the character of Berger from Keith Glass in the Sydney production of Hair. Two years later, he took on Herod when Jesus Christ Superstar transferred from Sydney to Melbourne. It was a very small part, barely more than one song, yet Reg insisted the part be expanded which still only took the amount of time he spent on stage each night to just nine minutes.

Reg became good friends with JC’s director, Jim Sharman. Sometime later, Sharman approached Reg about a new musical. Sharman had directed the London production of Rocky Horror and played Reg the soundtrack. Sharman wanted Reg for the lead – Frank N. Furter.

This new project was certainly a world, or rather a universe or two, away from JC. He immediately signed on and rehearsals began. Sharman purposely kept his cast in the dark on the matter of characterisations, instead allowing them to find their own paths.

Tim Curry, unbeknownst to anybody in Australia, had drawn on Joan Crawford as an inspiration for Frank N. Furter. Reg went the full Grand Guignol, calling up an entirely different old-time screen queen – Bette Davis. But this was the Bette Davis of Whatever Happened To Baby Jane rather than Dark Victory.

It wouldn’t be the first time he would channel Bette; later, for his inaugural one-man show, The Betty Blokk Buster Follies, Betty (played by Reg) was also very much Bette Davis but this time with the authoritarian undertone of a Nazi prison warden.

For Rocky, once Reg settled on Bette Davis as a suitable role model: “…it quickly opened the right doors, filling out the performance in ways that had been eluding me. It was the licence to kill; it gave me the walk, the strut, the stance, the voice, the delivery, and I think in the end I took the venerable Miss Davis where even she hadn’t dared go.”

In Reg’s Chapters and Chances, he wrote: “The role of Frank is obviously a gift for the right actor. I took it with both hands and shook the life out of it.”

Previews began and word soon spread that Rocky Horror was unlike anything ever seen before on an Australian stage.

The final preview started at 9pm, Friday 19 April, 1974, with the official opening following at midnight. Reg owned the show immediately and the rest of the cast weren’t too far behind. The sonorous Arthur Dignam was perfect as the narrator, Kate Fitzpatrick and Maureen Elkner shone as the sexy, conspiratorial alien handmaidens, Sal Sharah (who was on the cusp of gaining national attention in a series of television ads for Uncle Sam deodorant) was suitably creepy, and Graham Matters, who Reg had appeared with in Hair, nailed Frank’s “latest obsession”.

The auditorium was festooned with plastic sheeting, scaffolding and a long runway down one side, giving the impression that bulldozers would soon begin demolishing the theatre. The actors clambered up, down, across and though the audience at breakneck speed. It was a gruelling schedule with most nights having sessions at 7.15pm and 9.30pm.

For the first few months, Reg played Frank exactly as the script demanded. Once he’d settled in, the ad-libbing began. Initially, it was just bits and pieces, then became increasingly lengthy and bizarre.

Although I have no idea how many times I saw Rocky Horror on its initial Sydney run (if you lived through the 1970s and can’t remember much about it, you really WERE there), Reg’s serpentine, Byzantine meanderings were one of the true delights. What Frank said and did often changed from performance to performance, and the audience was never quite sure what would happen next.

The Sydney season ended after 18 months, closing October 4, 1975. Reg had bowed out, burnt out if truth be known, after nine months, and Frank N. Furter was henceforth portrayed by Trevor Kent, Andrew Sharp and Max Phipps. It wasn’t the same. Eric Dare, who owned the New Arts Cinema and leased it to Harry M. Miller for Rocky (as well as being an investor in the show), then bankrolled Reg in a one-man show at another rundown movie palace he owned, The Bijou at Balmain.

The Betty Blokk Buster Follies opened on Wednesday April 16, 1975, while Rocky Horror was still running at the New Arts. Reg wrote a series of characters, backgrounded their foibles and largely ad-libbed them to life. The show was seeded with songs by Lou Reed, Elton John, Paul Williams, Charles Aznavour, Billy Joel, Leo Sayer and others. The soundtrack double album went gangbusters.

Betty was the first of Reg’s one-man shows, continuing on with Wonder Woman, Sacred Cow and Firing Squad. Most ran at Eric Dare’s Bijou.

Meanwhile, Rocky Horror transferred to Melbourne and the venerable Regent Theatre, opening Friday 24 October 1975. Max Phipps was Frank. Sal Sharah and Graham Matters were the only original cast members to make the trek south. It was another great hit, running in Melbourne for 17 months until closing Saturday May 28 1977.

Rocky looked to be part of the Australian national theatrical landscape for some time to come. Then the unthinkable happened.

Adelaide happened. Rocky opened in August 1977 but the response from the fair burghers of the City of Churches was far less than enthusiastic. It closed two months later.

Let’s dwell on this a moment. South Australia, home to the Truro serial killings; the Snowtown murders; the Family – a well-connected cabal responsible for the kidnapping, abuse and murder of teenage boys; the local police known to have bashed gay men before throwing them, often dead, into the Torrens; the disappearance of the Beaumont children; and various gangs of local teenagers who regularly broke into the Adelaide Zoo to massacre the animals.

Salmon Rushdie, someone who recognised darkness better than many, called Adelaide: “…the perfect setting for a Stephen King novel or horror film.”

Adelaide, the City of Churches, didn’t warm to depictions of degenerate sex and violence on stage. In real life, however, it was a different matter.

But Australia wasn’t finished with Rocky Horror. The first regional production of Rocky occurred in 1978 in Wagga Wagga. And within a few years, it was back in the capital cities. The 1981 Sydney revival saw Daniel Albineri played Frank for the first (though not the last) time. It was also the beginning of a trend for the Narrator role to be a revolving door for local celebrities; the 1981 revival featured Stuart Wagstaff, Molly Meldrum and Noel Ferrier. Subsequent revivals have seen such narrators as Gordon Chater, Bernard King and Kamahl.

By the mid-1970s, though, the cat was well and truly out of the bag as far as Tim Curry was concerned. Australia had been shielded from Curry’s career-making characterisation of Frank N. Furter with the exception of the London cast recording.

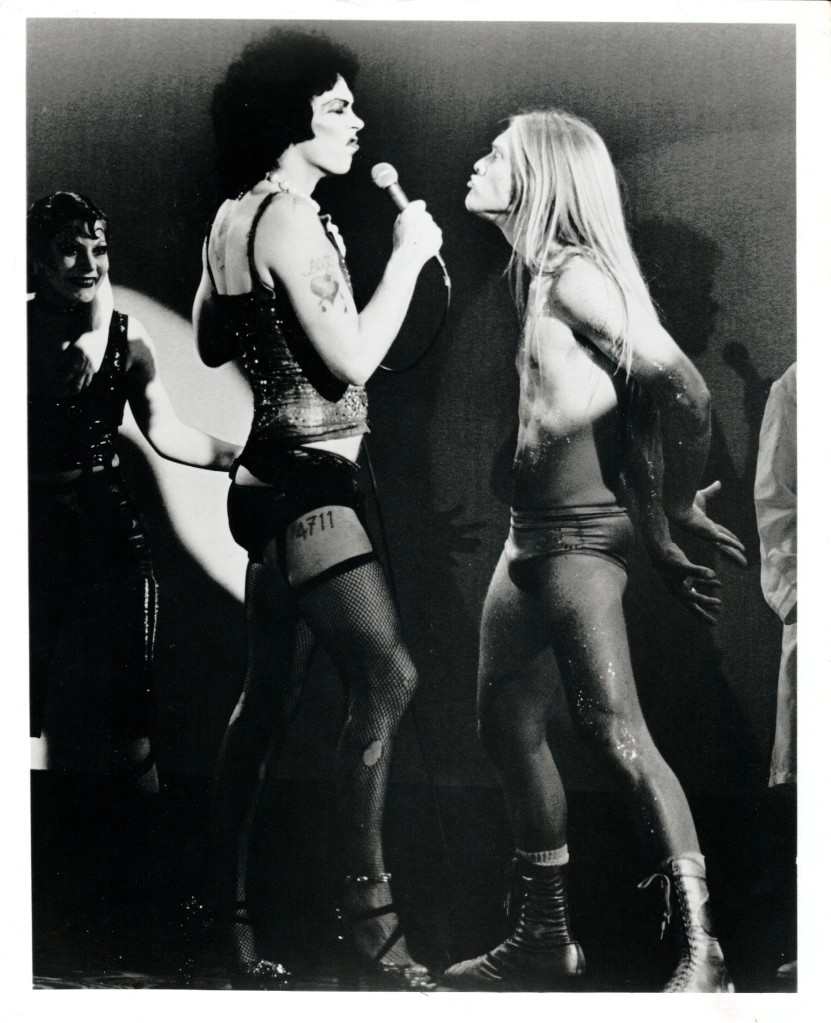

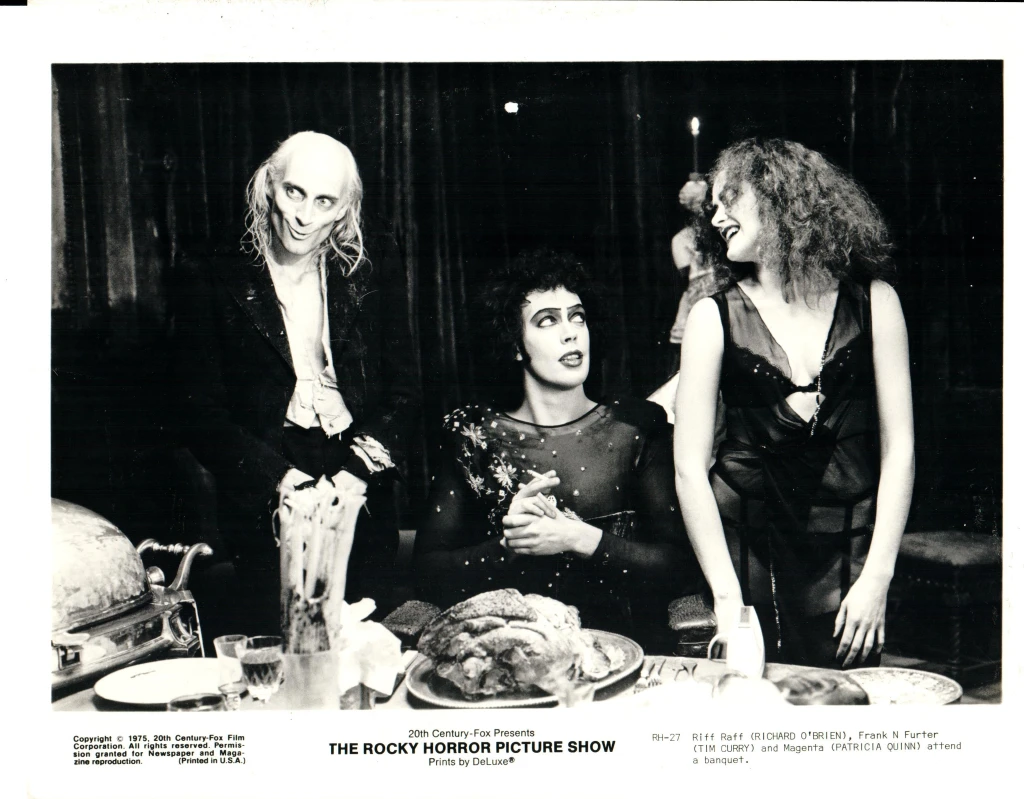

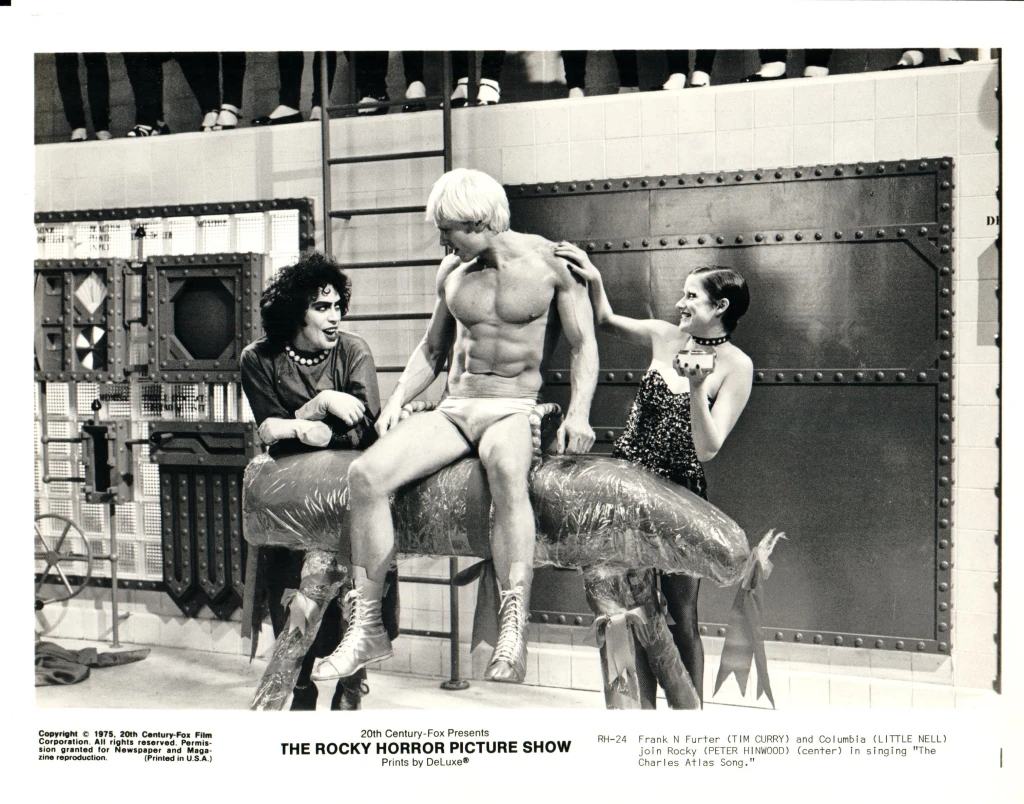

Jim Sharman was there from Day One. He directed the inaugural production of Rocky Horror in London, assembling a cast that included Curry, Patricia Quinn, and Little Nell. New Zealander Richard O’Brien, who wrote Rocky Horror, played Riff Raff.

The Rocky Horror Show opened small, in a 60-seater studio space above London’s Royal Court Theatre in Sloan Square. It ran there in June-July 1973 before word of mouth and skyrocketing ticket sales necessitated a larger venue. In August 1973, it moved to a 230-seat disused cinema in the Kings Road, Chelsea. Then, in November, a few streets away to the 500-seat Kings Road Theatre, where it played for five years. In April 1979, it moved to its final London home, the Comedy Theatre in the West End.

Curry would become the definitive Frank N. Furter although that would be a little way into the future. He left the London production during the Kings Road Theatre residency. He was replaced by Philip Sayer, who would be referenced to Australian theatre goers via the Sunday Mirror newspaper article, published in the run-up to the opening of the Sydney production.

Curry transferred to the Los Angeles production that opened in March 1974 at the Roxy nightclub on the Sunset Strip. Record company executive Lou Adler had taken in a performance in London in the winter of 1973 and immediately obtained the rights for an American production.

It opened Thursday March 21 1974 (three weeks before the Sydney production) with Meat Loaf as Eddie and Kim Milford as Rocky. It ran for nine months and attracted celebrities and movie stars backstage after every almost performance. Meat Loaf recalled meeting Elvis one night.

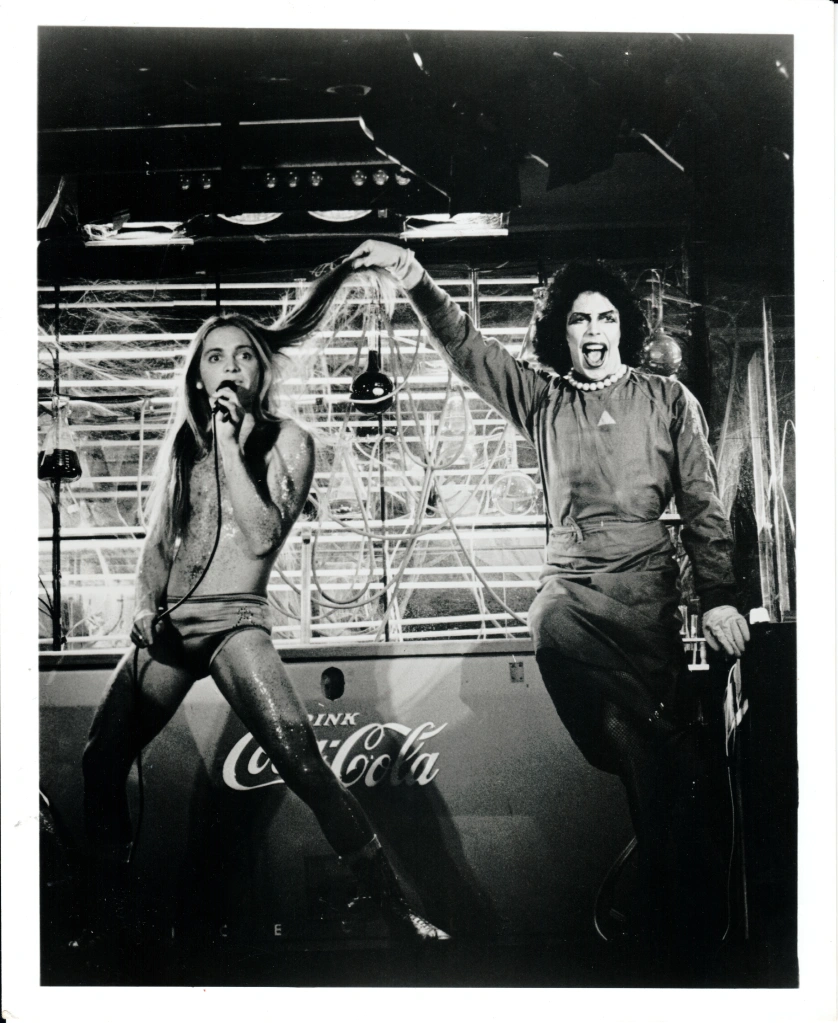

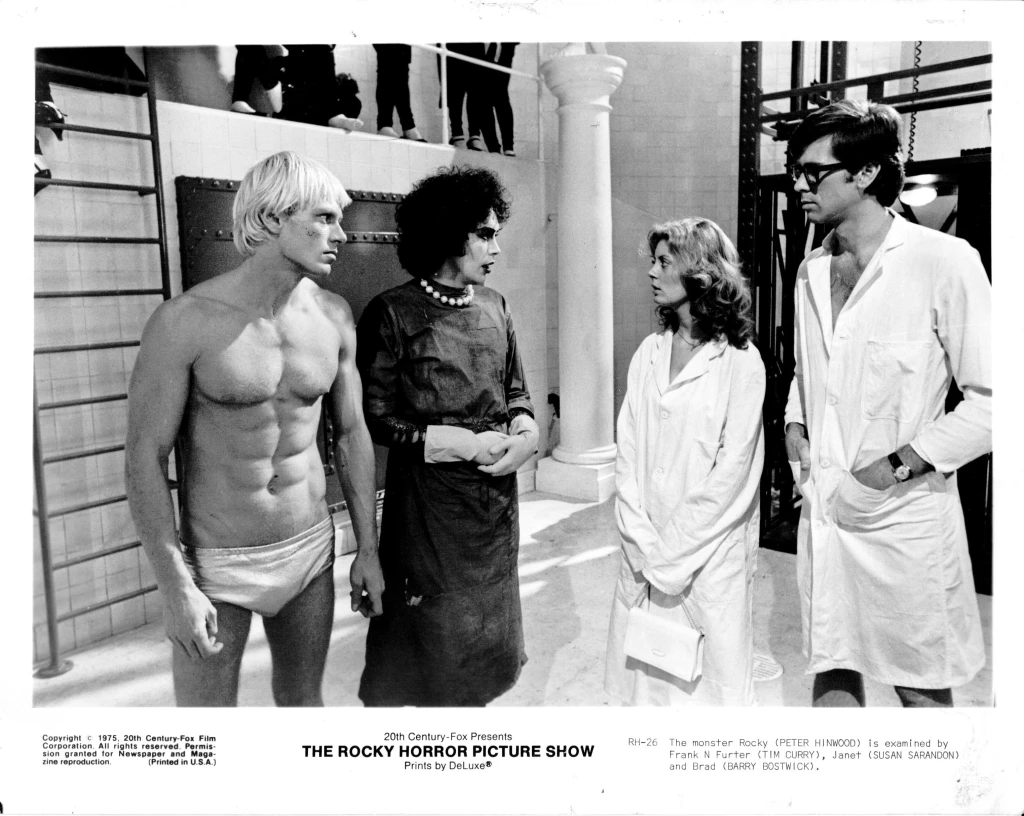

Adler obtained funding for a film adaptation and, in October 1974, Curry returned to the UK to commence filming. He starred alongside Patricia Quinn, Little Nell, Richard O’Brien, and Meat Loaf with Jim Sharman again directing.

Curry then went back to the US. On March 10, 1975, Curry opened at the Belasco Theatre in New York City. Rocky Horror had finally made it to Broadway after being a runaway West End hit. Yet something went wrong and it’s difficult to know just where. It closed on 5 April after just 45 performances. New York City and Adelaide. What to make of such indifference?

Perhaps Rocky’s appeal was over-estimated. The stately Belasco Theatre, erected in 1907, seated just over one thousand people. It was obviously a tough ask filling the theatre each night. Maybe it needed a smaller, more intimate venue.

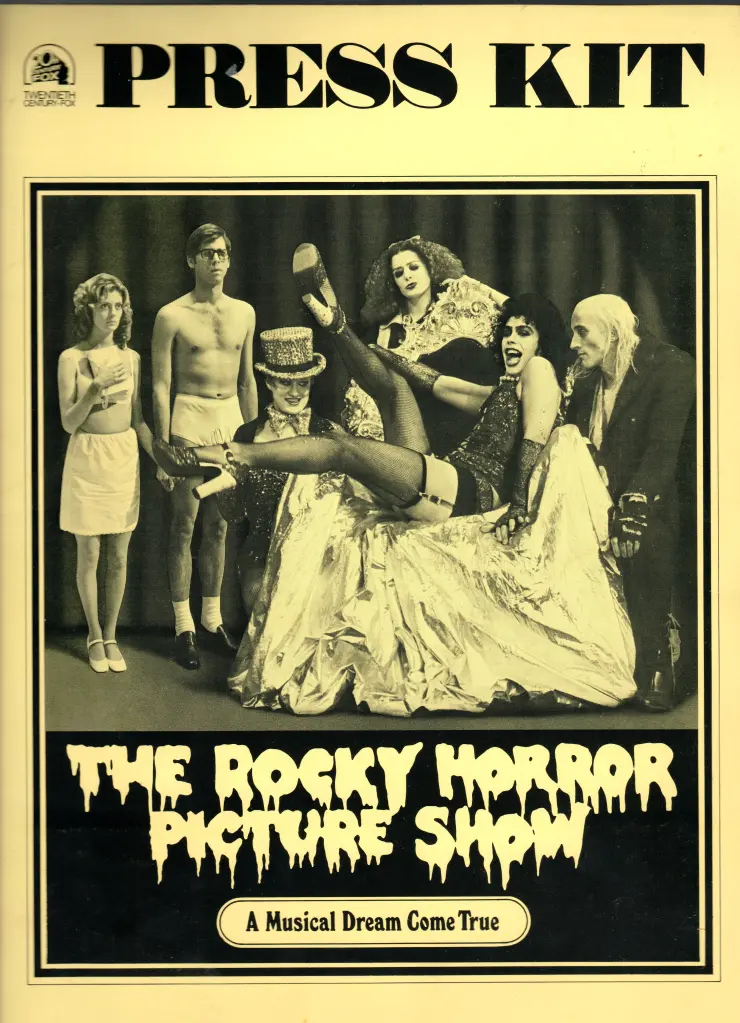

As confronting as it was bombing on the Great White Way, another shock was in store a few months later. The Rocky Horror Picture Show premiered in the UK on Thursday 14 August 1975 to almost universal critical disdain and miserable box office. The studio, which had no idea how to promote it, turned its back and left it dangling, like a corpse hanging forlornly at the crossroads.

It opened in the US on September 26 to similar reaction. Australia had to wait three months. It premiered in Sydney at the Ascot Theatre on 19 December. It did better than in many markets, showing for almost a month and closing on January 15 1976.

And although it was initially written off by the studio as a flop, we now know The Rocky Horror Picture Show to be one of the most screened films of all time. Somewhere in the world, it’s still showing and audiences are just as enthusiastic and committed as they ever were.

As much as I loved the Sydney production, I love the movie even more. I must have seen it hundreds of times. Curry is the ultimate Frank, a sweet transvestite of unparalleled excellence.

The big surprise, certainly for Sydney audiences who knew Reg Livermore’s Frank so well, was in confronting Tim Curry’s interpretation.

That surprise extended even to Reg himself.

As he noted in Chapters And Chances: “Some years after I quit the show, I finally succumbed and saw the movie version; I was shocked and surprised to observe how beautiful Tim Curry was. Nobody ever told me Frank N. Furter was supposed to be attractive; I went out of my way to make myself as grotesque as possible.”

Different strokes, as it were, for different aliens. Regardless, Rocky Horror continues to dazzle and its appeal cuts across generations always ready to do the Time Warp. Again. And again. And again.

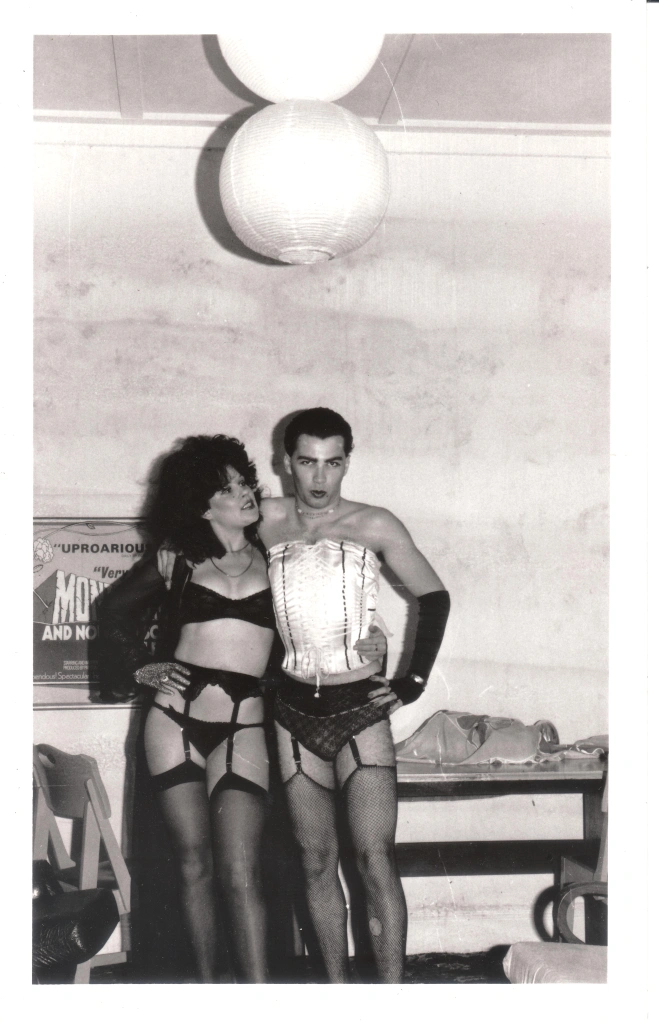

Postscript: Inevitably, Frank N. Furter became a favourite subject for fancy dress parties.

Photos courtesy of the Glenn A. Baker Archives and the author’s own collection.